Essay: A Last and First View, Connemara

Now, after long wanderings [philosophy] has regained the memory of nature and of nature’s former unity with knowledge… Then there will no longer be any difference between the world of thought and the world of reality. There will be one world… ~ Schelling

My foot has never alighted onto this soil in the Conmhaicne Mara, Iar Connaught. I’ve never seen it with my own eyes. Yet, I’ve dreamed of it if to dream is to know a place before you’ve ever arrived, to feel in it, stone ruin to tree to human, a sovereignty, a divinity and world coexistent beyond the seen—in your bones as memory and fate. Just as when I sit with you in the haven of green trees, flowers and vines, alone in a beauty and feeling spoken between us through time. A beyond-speaking as the rustle of silven trees moves with the wind. When I return, the stone may speak to me in the voice of an ancestor, if I can hear a story in the place, the cadences of language that existed and may still exist. What am I given to do in that land, on that island? I can listen to you from great distances in a thread in time, so that twenty years is another lifetime and only a moment—so that to see one another again is yesterday, and also tomorrow. The land calls me, calls me back, for it is open enough still, neither hacked nor blunted in the material dissociation. It exists beyond and within time and space, as an incontestable substance between air and rock and tree and weather which has always been—and was once known and lived alongside this singular world we think of as reality. In it, there is a knowing, a being, a feeling and a speech beyond hierarchy or duality. Rather, it is a circle, a veil and all things and beings exist within and through it, like the freedom and wilderness of space, but on Earth. We lose our edges and to be there is only being, alongside the element and vibration of things, their consciousness. As water is—each stone and tuft of grass is a nexus. We can go, too, for the body is an opening. It has always been. A part of me has always existed (here, there)—I’ve never left. When I walk alone, outside, it is so. We must find it again, unwinding suffering from before into the Oneness; we always seek it. Each rock is humming, rock, rock, our home that coalesced from inertia. The body in its impulse can do it, just as plant or sea can.

Your face arrived like the sun before me, and your mind, as it had always been—kind and keen and intelligent, unspoiled and idealistic. There is the listening there, in the air, the possibilities of the electric brain, the being we had been doing for years outside of time. Like a heavy blush of fragrant lilac in its spectacular weight in the palm, what isn’t known yet but already acquainted angles itself in consciousness between minds beyond the calendar, through the space of distance and land. Would I arrive before you like the smallest swallow curving on the easy seven o’clock breeze of late May, near what appears to be the horizon and the painter’s brushstroke of translucent blue, a studding cloud? It glows. I may arrive in Ireland over time and unknown, yet familiar and home. There is the far top of a brown chimney and the peaking gray of a cottage roof through the hedge of lilac, which meet and continue this sanctuary of green, Connecticut. You are my home, akin with this and that far thing I enter outside—and in the laying on of hands. To find a heaven on this Earth, we reach through to another space humans once knew.

I didn’t have the names and places, nor the papers always made about people that prove they existed. I had to go back to find them. For years before I went the first time (only a day), they kept arriving as the absence of a name or town, the question, the missing information or unspoken secret, the conversation I could never have, the migration unmapped. They kept arriving in the years after until I returned to search for them on foot. Still, such things remain hidden because it is their nature. One thatched cottage was no different than another, one hundred, one hundred and forty years ago. They were unremarkable, the most common home, thousands as such, in that seeking my great great great grandfather’s home, even with a photograph, it remained hidden. Even the streets have no names and no numbers; there is a hill or a mountain, there is its view noted on a letter’s heading, there are the gravestones I couldn’t find among five cemeteries—for a particular parish priest served and serves five such towns. The archaeological landmarks, however multitudinous, unique or common, were mostly hidden as well or only visible on a map, belonging in the yard of this farmer or on a hilltop through pastured green meadows and five gates, not visible from roads. Still, people traverse them—hillwalking is the unspoken rule. The Earth is whispering, the literal dirt is whispering, it holds close what is sweet, potent, once voluble, electric in the earth, known by peoples long ago. It will not divulge, for the land is unaltered, the stones that make the shape of each site—ruined house, cillin, ring fort, unconsecrated or consecrated cemetery, standing stone, ruined church, castle, well, passage tomb—are the same and make the land. They are not separate from it, but are the land, the people. So one may travel as and in energy to a place before, to a place beyond or in the spirit of each blade and magnetized iron furr.

Each arrangement of stones and earth was made for the daily, and the other realms, multimodal worlds, because only conceptions of dimension limit us with/in time. Each name is what we call them, but their location in the countryside is no metageography. It cannot concede north or sound, is hardly locable/located, and deems no power with a name. Each name is the same as repeated and together, the aerial view is most like chaos theory. No one can own them and no one wishes to.

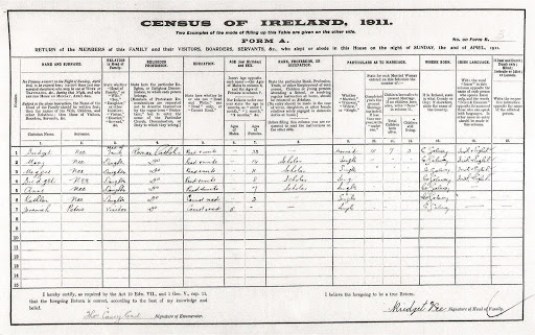

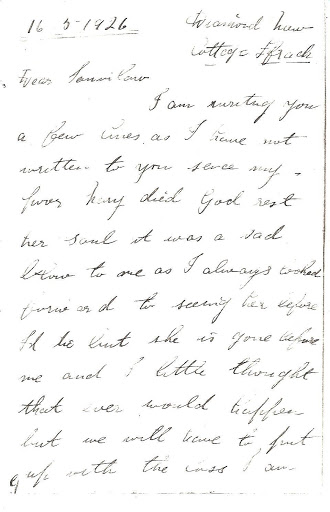

I found them in books and on websites, the names and the stones, in the scanned remains of marriage documents and property records, in boat manifests, in censuses and in photographs left behind by second and third cousins, their original letters in voices I could not really imagine. I had to go back because of the loss of memory in the family after suffering (as with all families)—we have not lost memory but we don’t have the bodies and the opening within to speak, to hear. Nor can we hear the dead, we lose places, people and their names. We forget the stones, their intimacy. We don’t know how to hold them. It is too difficult to stand in the pain of people or their absence, yet impossible to not. Pain is everywhere—in the rocks in our backyards, covered in moss, which we do not see. So is pleasure, so is the nothing. In the success of oppression, we began to unlearn the language of intimacy, the warm circle of home and bodies, their soft, furred thoraxes exposed so tenderly. The rock is our ancestor, is a beacon and a telephone, an ocean and a chime through time. How the Japanese Knotwood rebalances the soil, so we should not kill it. We forget how to caress the one we love, and we can’t feel our mother’s embrace, no matter how hard we try. The rocks might be nothing in our new American or Irish homes. Even as they sit, they sift through the landscape—and the landscape speaks.

I slept in villages that were a road, a slip of narrow dirt to another village inside a parish or a town—and any of the houses could be a collection of stones humming my family name. Each village was one. It is only the American who searches and finds it remarkable to collect the stone, walk the lane, or speak to a far cousin descended from the brother of a fourth great grandfather. Or is it? That is a lie. There is so much in America, and we are mostly a country of immigrants, where to come is to arrive unable to keep two narratives, two names, even though we must. The spelling isn’t the same and what we thought we escaped may be what we missed. It’s not nostalgia, however potent and real, but longing, like the vowels we want to hold in our mouths. It’s the stones and how they speak when we touch them. Even without them, (are they markers for feeling, experience, travel) it is possible to go. In the history (our brains), there is being on the land, in the silence of green and what was before, even if we don’t know it, and we can’t tell it. I’ll tell a little of my own. They took a last look and it is clear why. They were starving and nearly lost from the land and their own ways, starved of their vital selves. They were sifting the Colonial. It is a thing anew, this Ireland today, for I took a first breathe in the wild—and I could. Places hold the weight of whatever came before, gift and slaved. Just as I came home to home, a New England. Don’t fear the wild. Listen to your new and old language.

My great-great-great-great grandfather lived in what is now Connemara National Park, 2,957 hectares of land, barren and plentiful, along the Wild Atlantic Way: mountain range, woodlands, blanket bog, lough, wet heath and grassland. Clifden and Letterfrack are served by the civil parish of Baile na Cille or Ballinakill, where a cemetery stands along the river Lee that feeds into the sea. My great great great grandfather, Michael and his daughter after him, Brigid, rest there, nearest to the small Catholic Church overseen by Father –, even still in 1930–. My great great grandmother, Brigid, mother of six, notes in a letter from 19—that she obtained the birth certificate of her sister to send back to America. She writes her sister and later notes that my great grandmother is excited to immigrate, having just had her immunizations. Michael Connelly wrote wry and sweet letters to his daughters abroad in America. You can tell how much he missed them, how he knew he’d never see them again before he passed to the grave—or they, too. It turned out his daughter Mary would die of cancer in Garden City, NY, before he would die. He wrote to her husband of his great sorrow in her death. Each letter has the heading of “Diamond Hill,” as was common for those living in town, for he lived on Diamond Hill, or Bengooria, Binn Ghuaire, “Ghuaire’s Peak,” one of the Twelve Bens mountain range in Ballinakill. In the Geographical History of Ireland by — published in 18–, —, the author, on his journeys surveying the far West of Ireland, County Galway near the Wild Atlantic Way, notes the residence of one M – Connelly, in residence on Diamond Hill, 18–, father of my great great great grandfather, Michael, husband of first Celia, then Margaret and father of twenty one living children. How strange to see their names in the document, noted by its painstaking author as he traveled on foot from cottage to cottage. I had been searching for some great time, and a map of the land collected like a census for humans and ice ages revealed this most familiar ancestral place.

In the 12th and 13th century, just as who we might call “the English” decided to begin colonizing Ireland, routing out the language from her people, we find the name of Connelly listed as part of the Mac Connemara—the descendants of Con Mhac, the (mythical) ancestor or “hound son”—the governing clans of the Western Kingdoms of Ireland. These were known as the Connemary, the parishes of Baile na Cille, Ballindoon, Maigh Iorras, Omey and Inisbofin. The MacConneelys were the eldest cadets to the O’Kealys, one of the main ruling families or tuatha of Ireland. They’d lived in this land, since before Medieval Times, until in 13–, when the land held by the Conmhaicne Mara was forcibly given to an English ruling lord who took it over, scattering the tuatha west and south, even nearer to the Atlantic. The people in the West of Ireland, more than any other region on the island, retained their language through seven centuries of British occupation and rule, despite the colonizer’s best intention at cultural genocide. Did they retain it? Historian Declan Kiberd says, “If every word was once a poem before being denatured by common use, then each sentence may also be a kind of epitaph on an emotion. In an analogous way, a nation state may be an elegy for a language, a secondary institutional formation designed to fill the void left by a lost language and by the structures of feeling which disappeared along with it.” They did not fully disappear.

That first time, I said, “I’m going,” aloud, as if to mark some boundary of movement back, nearly the first such movement since my great-grandmother had come on the Carminia in 1920. That was six years ago, and I stayed for a long, full day and a night, and then returned to England. The second time, with you, marks less than a week before we land in Cork, then drive up through Kerry the next day and overnight in Sneem, through Cahersiveen, then on, straight up the coast and Wild Atlantic Way to Galway, to sleep in a ring of places where my blood once rested: Clifden, Dawros More, Renvyle, Letterfrack. There are mountains and hills, inlets and rivulets, the Atlantic and shallow, studded small islands off the coast, National Park and high mountain flower, dropped lakes from the Ice Age and the white marble-dropped country of liminal land and hardy, challenging soil which my third great grandfather worked so hard for all of his life: rocks, rocks, rocks everywhere made into things of use for living, praying, being, sitting, and keeping ancestors, both held and in disarray. This disarray isn’t different from their original organization. In such a language we speak of stone and water and roads as endless ways for expressing human ties. Stones are dropped and found everywhere on earth, made into fences and walls, carved and held in places to consecrate with nature. As a place, a stone may hold the sound of what came before. I’ll tell you how it speaks.

When I arrived, it was as if the place was empty. Empty of all of the traces left by people, the small dashed pathways on land and spirals through air where we’ve moved again and again, consuming the spaces in a place until such pathways make a hectic map blocking out all of the trees. There isn’t even a tree left. The map is all we see. Is it normal? We don’t see the trees as they have become background filler, and the dirt too, the water and rocks, the prism of sky in its depth, the land that rolls and continues in every which way, populated with the speech of stones, until one hits ocean. We see ourselves, but maybe we don’t either. I don’t see you and I don’t see the tree. The stones are dead to me and that is the worst. I think I am so different from the stone, born for great things and money and a name, that I can’t even see myself in the midst of the nature. It is my bone, my dust heated and transmuted through the pull of the universe into the stone. When I say I, I mean we. These are the stories we tell ourselves, where we don’t walk with our own feet and we can’t see out with our eyes. We go in. What if we walked out, we explored without anything? The internet was a terrible invention. It will save us, perhaps, but still—it is a terrible invention for the brain. What is it like to be free? Can you remember, now, what that felt as in your nervous system? To not think of yourself as yourself within the view of thousands, your story, your face, you, you. To simply be, like a leaf in the lip of the water current, one heart alone but in unity. What is natural? Can you remember? What if our pathway was quiet, a small dashed line like a choreography between trees and parallel the river, still in the music and vibrating in the places that are known to be of our Qi. Or soared in a car and then doubled back, offending no one. What if we went on foot, with the whole sky always above us, a dome of gloaming, radiant ions—

This is what it was to go back. The sky was more alive than most places, as if the place still remembered its name, as if the trees and grass-ridden valleys easing up into hills and pockets holding more stones were the place, rather than our arriving making it so by evidence—as they are and always have been. The sound of land and geo, earth, was stronger than anything else. What is it like to arrive in such a place, when the places with which we have union have been obliterated and so have we? We can’t feel them anymore. We don’t know how, most of us. They can’t speak as they once did. What is it like to arrive in such a place? It is like dying—the death of all that we have made—and then we are born again.

Melissa Buckheit is a queer poet, translator, activist, dancer and choreographer, photographer, English Lecturer and Orthopedic Massage Therapist. She is the author of Noctilucent (Shearsman Books, 2012), and two chapbooks: Dulcet You (dancing girl press, 2016) and Arc (The Drunken Boat, 2007).